THE RUNNER

Artwork courtesy of Silvermoon Mars LaRose, Narragansett (2025)

Where History is Shared and Stories Continue

July-Sept. 2025

“The Runner” acknowledges and honors traditional ways of sharing news.

Kunoopeam Netompaûog

Welcome Friends

Hello Readers!

I hope you are enjoying the quarterly issues of The Runner. In this 3rd quarter, we are sharing how history shapes our present and is preserved through cultural expression (art).

I searched the internet to see who would come up under “famous artists in history.” I wasn’t surprised by the result. You probably know some of the names: Leonardo da Vinci, Pablo Picasso, Rembrandt, Georgia O’Keeffe, Vincent van Gogh, Salvador Dali, Michelangelo, Johannes Vermeer, Edvard Munch—the list went on, with 42 more names just like them. What did surprise me was that the list extended all the way to artists born as recently as 1960. Still, not one of the 51 names was Native American.

It made me pause. We continue to learn about these iconic figures in classrooms, museums, documentaries, and coffee table books. Their work is valued, preserved, and elevated as “fine art.” But where are the Native American artists who have been creating all along—historically, fundamentally, and continually? So I searched “famous Native American artists in history.” Eight names were shown, and not all of them identified as Native American. So I searched a little deeper until I found, Fritz Scholder, Allan Houser, Norval Morrisseau, T.C. Cannon, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Kay WalkingStick, Wendy Red Star, Maria Martinez, Charles Loloma, Jerome Tiger, George Morrison, John Hoover, Edna Massey, Patrick Suazo Hinds, Kent Monkman, Marie Watt, and Frank Buffalo Hyde all representing various Tribal Nations from the East Coast to the Northwest Pacific. I invite you to look them up and read their bios.

In this issue I’m adding to that list by spotlighting some whose work continues to shape identity, holds memory, and preserves culture. This is about more than art. It’s about honoring a legacy that has always existed, even if history has tried to leave it out.

PRESERVING HISTORY THROUGH CULTURAL EXPRESSION (ART):

Native art is a powerful form of cultural expression that exists in diverse forms, traditions, and representations. It often reflects a deep connection to spirituality and the natural world. These art forms include—but are not limited to—basketry, quilling, beading, pottery, shell, and carving in wood and stone. Each piece of art frequently tells a story, serving as a vital means of preserving and passing down cultural knowledge.

Today, Native artists continue to work in many of these traditional mediums while also embracing contemporary methods to address modern themes and issues. Some blend the old with the new; others create entirely through contemporary styles. Regardless of medium or style, it is Native art because the artists themselves are Native—carrying with them ancestral knowledge, lived experiences, and personal expression.

Legacy in Stone

Indigenous Veterans Monument, Exeter, RI; Craig Spears Masonry and Angel Beth Smith, Artist (installed 2023)

The ancestors of today’s Narragansett people have been shaping stone for thousands of years. Through generations of thoughtful artistry and utility, their modern descendants continue to demonstrate an inherent skill in working with stone. Today, Native stone masonry in New England is recognized as one of the tribe’s traditional crafts—a legacy of creativity, strength, and enduring labor.

Narragansett granite stonework is woven into the land itself. Beautiful walls of stone snake through marshes, woodlands, and farmland, undulating and blending with the natural terrain throughout the ancestral homelands of the Narragansett, now called Rhode Island.

Narragansett Indian Church (2024)

A particularly important site is the Narragansett Indian Church and Meeting House, the community’s spiritual and cultural stronghold. Originally built of wood in 1750 by Narragansett men, including Samuel Niles—the church’s first preacher—it was later rebuilt in 1859 after a fire. This time, it was constructed with granite block walls sourced from the local Westerly quarry, then transported by cart, oxen, and Narragansett hands to its current location in Charlestown.

This tradition of stonework is more than architectural—it is cultural memory made tangible. Stonewall John, the first recorded Narragansett stonemason, is best known for building Queen’s Fort—a stone stronghold constructed to protect Saunksqua Quaiapen and other surviving Narragansett and Wampanoag people in the wake of the Great Swamp Massacre during King Philip’s War.

Today, that legacy continues. What once served primarily utilitarian purposes—offering shelter, defense, and structure—has evolved into a form of cultural and artistic expression. Stone walls, columns, fireplaces, and other forms of masonry now stand not only as physical structures but as cultural monuments—testaments to endurance, skill, and the ongoing preservation of Indigenous knowledge.

Legacy in Clay

Another powerful example of preserving history through art can be found in the continuation of Indigenous pottery traditions. Originally created for practical, everyday use—such as storing seeds or cooking—these vessels have evolved into profound expressions of cultural identity and resilience.

Courtesy of Tomaquag Museum Archives

Pottery is more than visual art; it is a vessel of cultural memory. Seed pots, for instance, once held heirloom seeds and were designed with small openings to protect their contents—ensuring the survival of the next year’s crop. These forms, once purely functional, now carry intricate beadwork, incised patterns, and symbolic adornments that reflect the personal creativity and cultural knowledge of each artist.

Brenda Hill, First Nations Tuscarora, Mohawk, Mississippi Choctaw & Cape Verdean artist; photo courtesy of Tomaquag Museum Archives

Traditional pottery methods use natural materials both in form and in process. Clay is gathered from riverbeds and glacial soils; textures are made using carved antlers, shells, stones, wood, and even plant fibers like pine needles. These tools and materials link each piece to its environment and to ancestral practices.

Artists like the late Diosa Summers (Choctaw) embodied this connection—hand-building pottery that incorporated traditional techniques alongside natural elements like feathers, leather, and plant life. Her work was not only artistic but deeply symbolic, representing shared Indigenous histories and contemporary identity. This tradition continues through her daughter, Brenda Hill (Enrolled Tuscarora, Choctaw), whose clay pots carry forward the practice while offering their own unique style. Her work—distinct from her mother’s—stands as a living example of how traditions evolve yet remain rooted in community and cultural continuity.

To explore this tradition even more deeply, we invite you to hear directly from a master artist. Click here to listen to Ramona Peters, Mashpee Wampanoag, who has been working with clay and creating beautiful works of art for many years. Her voice and story add powerful insight into the enduring relationship between Indigenous people and the land through the medium of clay.

Legacy in Beading and Moccasin-Making

13 Moons Puckertoe Moccasins, photo courtesy of Mishki F. Thompson, 2025

In our ongoing exploration of how Indigenous communities preserve cultural history through creative expression, we spoke with Mishki Thompson, an Enrolled Narragansett Tribal citizen and beadwork artist, who shares how her art is deeply rooted in heritage, storytelling, and community values.

How does your art reflect or preserve your cultural heritage or tribal history?

“When I make moccasins, I use deer hide and sinew—materials our people have used for generations,” Mishki begins. “I recently made a pair for Tomaquag Museum choosing the traditional pucker toe moccasin style. I wanted them to reflect something meaningful—not just to me, but to our Tribe.” As she reflected on what elements could best represent this cultural continuity, she landed on the idea of honoring the moons and thanksgivings. “We celebrate the Strawberry, the Cranberry, and the Nikommo moons. I thought it would be powerful to express those in beadwork, so I did.”

Each stitch became an act of remembrance and reverence, bringing together tradition, ceremony, and creativity. “It’s not just decoration,” she adds. “It’s a visual way to tell our stories.”

In what ways do you see your work as a form of cultural expression?

Beadwork, for Mishki, is both a personal and collective practice. “I started around 2015, thinking I could save money by making my own pieces. But I quickly realized how much time, skill, and cost goes into it. It gave me a new appreciation for our art.” Her style is simple and accessible by design. “I don’t do intricate patterns. I can’t draw, and I try to keep my beadwork affordable so people in and outside of our community can enjoy and support our culture.”

She explains that this simplicity isn’t a lack—it’s a reflection of her purpose. “I do this because it connects me to who I am. I didn’t grow up dancing at powwows, but I always knew who I was. This is a way for me to stay rooted in that and help my kids do the same.”

What stories, teachings, or values are you hoping to pass down or highlight through your art?

“Beading became something I could do at home, something traditional my kids could see and be part of,” Mishki says. All three of her children have learned how to bead, and one has embraced it fully, creating pieces of their own. “It’s important that they know where they come from. I want them to be proud of it.”

Beyond her family, Mishki shares her knowledge with the broader community. She regularly teaches beading classes, welcoming both tribal and non-tribal participants. “It helps people understand our art, our values, and that it’s okay to support and wear Native-made art. It’s a way to help keep our traditions alive and care for our families.”

Through her moccasins and beadwork, Mishki Thompson carries on a quiet but powerful form of resistance—preserving history not only in museums or books but in every stitch, every moon, and every shared story.

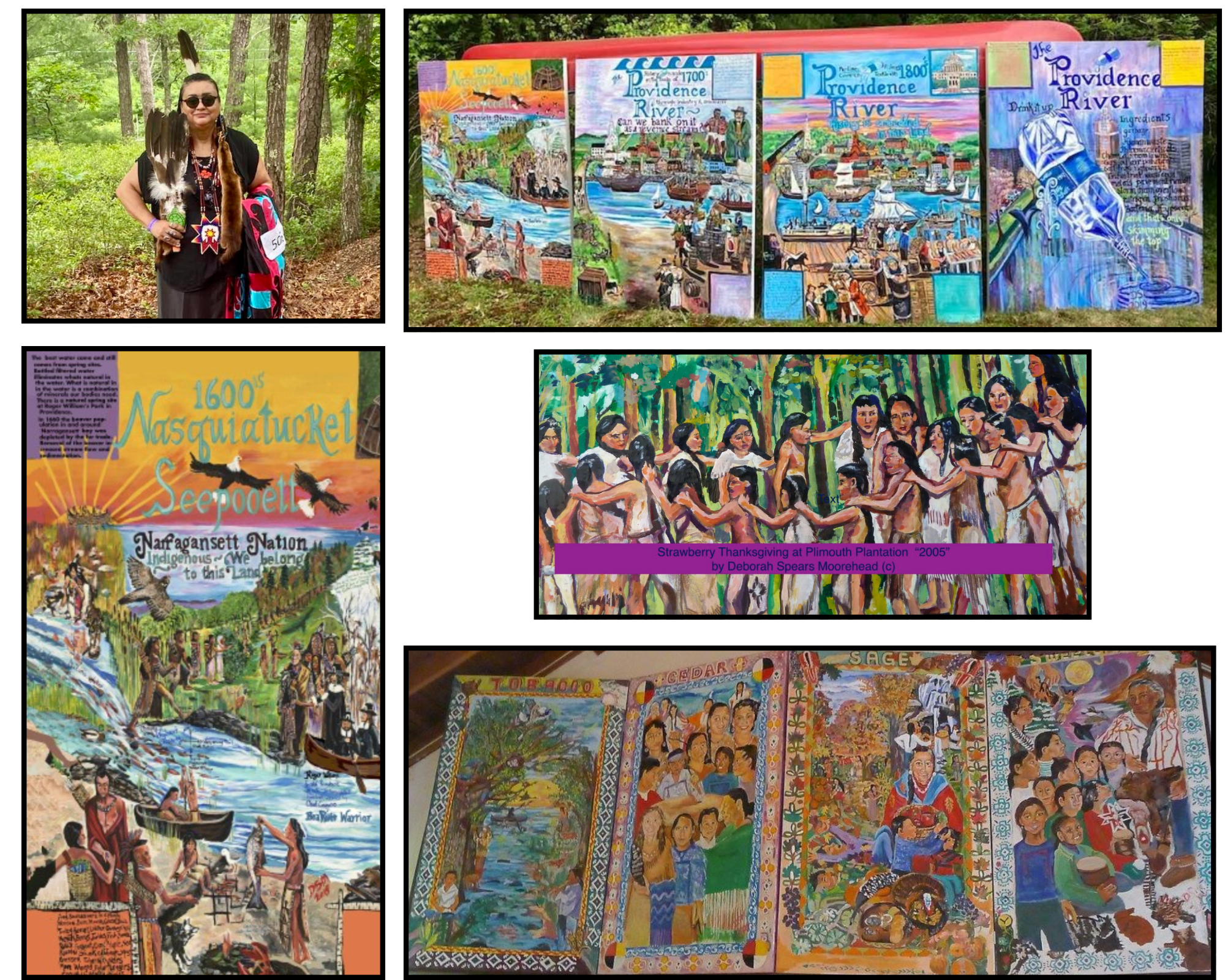

Legacy in Paintings, Drawings, Murals, and more

There are so many wonderful Indigenous artists who are not limited to just one single art form, but are multi-talented I was unable to interview for this issue. However, I am highlighting their beautiful works through imagery that speaks for itself. Cultural connections through faces, environment, and colors are a reflection of the natural and spiritual world we live in and clearly exemplifies their connections to their cultural heritage. Enjoy these images that tell stories of past, present, and continuation.

Dawn Spears, Choctaw/Narragansett; photos sourced from Dawn’s website.

Dawn Spears, Enrolled Narragansett, Choctaw is a talented artist working across diverse mediums, including painting, murals, corn husk dolls, and wearable art. Her work reflects cultural depth and creativity you can see, share, and wear.

Learn more about Dawn’s art by visiting her website. To explore her personal cultural connection, visit [Project Antelope]—just click here.

Deborah Spears Moorehead, Pokanoket, Seaconke, Wampanoag; photos sources from Deborah’s website.

Deborah Spears Moorehead is a direct descendant of Massasoit. Deborah’s art, music, literature, and sculpture assert the past, present, and future of the Eastern Woodland Native American people. Every piece of her work is authentic and presents its own story. Deborah’s style is unique and very recognizable. All of her art comes with a Certificate of Authenticity signed by the Artist. Here are Deborah’s own words from her website. For more about Deborah and her work, please visit this site for an interview between the artist and cultural survival.

There will never be enough pages or time to fully honor the incredibly talented and gifted Indigenous artists who continue to celebrate and preserve their cultures through the work of their hands. From cooking, book illustration, storytelling, and writing, to quillwork, finger twining, gourd painting, woodworking—and so much more—each creation is a reflection of the Creator, and of each artist’s deep connection to their ancestry and homelands.

Art is more than expression; it is testimony. It tells the world that we are still here—that our traditions live on, evolving with the times but rooted in who we are. To all the amazing artists: thank you for your contributions. Your work serves as a powerful reminder to honor our ancestors, Mother Earth, Father Sky, and one another.

~Chrystal Mars Baker, Education Manager

SARARESA SHARES:

(a new quarterly addition)

It was 1979. I was a 10-year-old fifth-grade student reading a copy of “The Diary of Anne Frank.” I could not believe my eyes when I looked at the black and white pictures of starving people being held imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp. I could not believe people did that to each other. I was so naïve and innocent back before I grew up in today’s ultimate circus crazy world. Despite having read that book more than 55 years ago at the Tuba City Elementary School on the Navajo reservation, Anne Frank’s words and legacy have stayed with me. The teacher who introduced me and my Navajo-Hopi Native American classmates to the Holocaust and Anne Frank is Ms. Carol Hornung. I remember her telling us her family story about her parents having to leave Austria after the Anschluss and emigrated to the United States. The Anschluss Osterreichs is German for the Annexation of Austria when the Federal State of Austria was annexed into Nazi Germany on March 12, 1938.

Back then as a 10-year-old, I was sheltered and grew up in a close-knit extended Navajo family where I felt safe and loved. As an inexperienced schoolgirl I could not believe people were so cruel to other people who are “different.” In my consciousness, I remembered what my cheii Buck Austin, a Navajo Medicine Man and community leader, was talking to my parents about the Navajos (Diné) being mistreated by U.S. Soldiers (siláłtsooí) and being forced on the Diné hwéeldi (“The Long Walk”). I understood the Navajo language because when I was a baby my Másááí (ShiMásááí means maternal grandmother) only spoke Diné Bizhaad (Navajo language) as a baby to toddler-age. After I thought about Anne Frank and other concentration camp victims, I thought about my own Nihízeezí(Diné ancestors) and felt a connection to Anne Frank and her plight. Since then, I wanted to read anything and everything about the Holocaust, Holocaust survivors and, of course, Anne Frank and her family. Today, I read Holocaust literature, books and website vlogs voraciously.

We, Tomaquag Museum colleagues, were fortunate to be invited to Providence’s Sandra Bornstein Holocaust Education Center on June 12 to listen to Dr. Laura Auketayeva’s presentation titled Holocaust in the Soviet Union. Dr. Auketayeva is the center’s Director of Education and Programs at the Sandra Bornstein Holocaust Education Center. Dr. Auketayeva, who is originally from Kazakhstan, is a Holocaust scholar. She was inspired to study the Holocaust by professor Steven Katz during her undergraduate studies at Boston University. Dr. Auketayeva also follows professor Katz’s teachings to be involved with rigorous scholarship, critical analysis and the irreplaceable value of survivor testimonies.

“His approach inspired me deeply, motivating me to explore survivors’ stories and experiences further,” Dr. Auketayeva said. “Building on this foundation, I chose to focus my doctoral research on Jewish refugees who survived in the Soviet interior – an aspect of Holocaust history often overlooked.”

Auketayeva said she studied how “Jewish refugees who fled to the Soviet interior during the Holocaust endured displacement, systemic discrimination, cultural disruption, and trauma,” Dr. Auketayeva said adding that, “thousands of European Jews fled eastward specifically because they were targeted as Jews during the Holocaust.” Once the Jewish refugees made their way to the Soviet Union, “they faced forced labor, exile, scarcity, starvation, and pervasive antisemitism in the Soviet interior, including Russia and Central Asian countries, and areas identified as Siberia.”

Dr. Auketayeva said that those Jews who stayed behind in Europe were murdered by Nazis and local collaborators. She said after World War II ended, the returning Jews who survived in the Soviet interior along with remaining survivors “frequently faced hostility from former neighbors, further displacement in Europe’s Displaced Persons camps, and significant challenges in rebuilding their lives.”

The commonality in Native American people and the Jewish people includes comparable in similar issues, societal challenges in relation to assimilation, religious rights and preserving cultural heritage. I believe the words of the assistant director of the Tomaquag Museum, Silvermoon LaRose, said it aptly, “Trauma recognizes trauma.”

As I reflect inwards, I believe she is right, I am the child of Native American boarding school survivors. As we learn about the commonalities between Native American people and the Jewish people, we can learn from their histories and live in hope that there is innate healing for the Native American people and the Jewish people.

By Sararesa Hopkins(Navajo Diné), Educator

BOOK NOOK:

I’m writing this newsletter from Minneapolis, Minnesota, where I had the opportunity to visit Birchbark Books—an Indigenous-owned bookstore that left me deeply inspired. I was blown away by the sheer number of books by Native authors. But what truly caught my attention this time were the illustrations—not just the vibrant book covers, but also the artwork within the pages of storybooks. These illustrations are powerful and moving; they are truly works of art.

t reminded me how often we overlook the artists who bring these stories to life visually. Many of these illustrators are Native, and their artwork is rich with cultural meaning, symbolism, and beauty. Their contributions deserve to be celebrated just as much as the stories themselves.

I encourage you to take a moment next time you pick up a book to appreciate the artwork, the lines, the colors, and the story they tell through image. I’m sharing a few children’s books to highlight the incredible work of Native illustrators whose art supports the words and messages written by the authors and continues the legacy of storytelling through a different, yet equally powerful, medium.

I Am On Indigenous Land

Author: Cheryl Minnema Source

llustrator: Sam Zimmerman Source

Sam Zimmerman is an Ojibwe artist from the North Shore of Lake Superior. He’s the illustrator of I Am On Indigenous Land, and his art is full of meaning, color, and connection to the natural world. Sam’s paintings are inspired by Ojibwe teachings, clan animals, and the land where he lives. He mixes traditional ideas with modern art styles—like abstract and expressionism—to tell stories in a new and powerful way.

In this book, Sam’s artwork helps readers feel the deep connection between Indigenous people and the land. Every page is filled with bold colors and symbols that celebrate Ojibwe identity and show that Indigenous cultures are strong and alive today.

The story was written by Cheryl Minnema, a member of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe. She’s a writer, poet, and beadwork artist who shares important messages about family, community, and culture. Together, Cheryl and Sam use words and art to remind us that the land we stand on has always been Indigenous land—and that it still is.

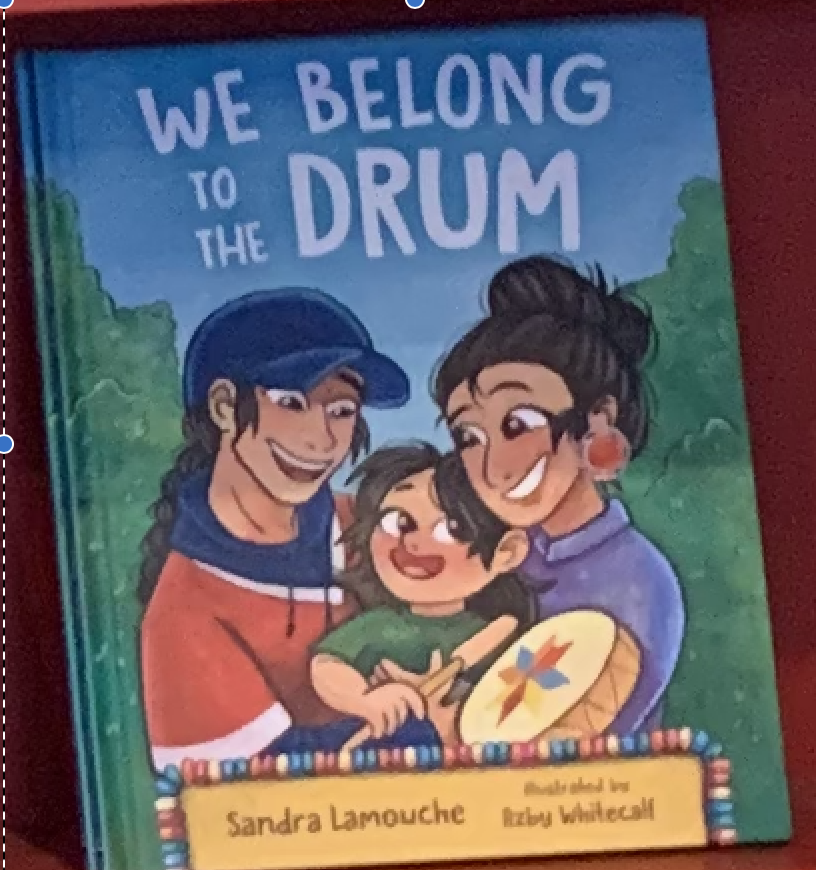

We Belong To The Drum

Author: Sandra Lamouche Source

Illustrator: Azby Whitecalf Source

Azby Whitecalf is a Plains Cree artist from North Battleford, Saskatchewan, on Treaty 6 Territory. She’s a character designer and illustrator who uses her art to tell fun, exciting stories filled with bright colors, bold shapes, and unique characters. But Azby’s work is about more than just fun—it’s also about culture. She focuses on creating accurate and positive images of Indigenous people, showing how strong, joyful, and multi-dimensional Indigenous identities truly are.

In her illustrations, Azby shows that Indigenous cultures are not just part of history—they’re alive, growing, and full of creativity. By blending traditional values with modern art styles, she helps young readers see themselves in books and feel proud of who they are.

In this book, Azby worked with author Sandra Lamouche, a Cree dancer who uses hoop dance to share teachings about respect, equality, and the environment. Together, they bring words and pictures together to help keep Indigenous stories and traditions alive for the next generation.

JUST FOR FUN:

Hey kiddos! Since we are celebrating Native American Art and Artists, you might like to try making some of your own! Corn husk dolls have been made for generations by Native Americans and they even taught newcomers who settled in Turtle Island. Oh, by the way, Turtle Island means the United States of America. Now back to corn husk dolls. Below you will find what you need and instructions to make your own. BUT—don’t put a face on your doll. Here’s an Oneida traditional story about why not:

Along time ago children were getting into trouble or getting hurt because the adults were busy and not watching them every second. The Creator fashioned a beautiful doll from corn husk to watch over them. Corn husk doll was not only beautiful, she could walk and talk, and she seemed like a real person. She took good care of the children and taught them many things. She entertained them with stories, played games with them, and sang them to sleep.

One day after a very heavy rainfall, Corn Husk Doll took the children outside to play. She spied her reflection in a puddle and was quite struck with her beauty. From then on, she only wanted to make herself even prettier. She stopped doing her chores and was only interested in having beautiful clothes and looking at herself in the water. She became lazy, vain, and selfish. The children were getting into trouble again because no one was watching them. The Creator warned her, and still she only thought about her looks. Finally, the Creator sent Owl to take away her face and her powers to walk and talk.

Today, the Oneida and other Iroquois people make corn husk dolls without faces so children can be reminded to think about other people and to chip in with chores and other responsibilities. Most of the dolls are dressed in beautiful clothing of a particular nation and many are prized by collectors all over the world.

Story and directions written in “A Kid’s Guide to Native American History, More than 50 Activities” by Yvonne Wakim Dennis and Arlene Hirschfelder

RESOURCES:

At Tomaquag we are continuously doing the work of educating new generations of children as well as the general public about the lives, traditions and life changes of the Indigenous peoples of Rhode Island and neighboring communities. Follow us on our website at tomaquagmuseum.org, Youtube and Facebook. Check out these resources!

For book reviews click here.

To purchase books and support an Indigenous business and authors, click here.

To support Tomaquag museum, other Indigenous businesses, and artists, shop our store here.

Did you miss previous Newsletters? Click the link below to read now:

Jan-Mar 2025 language, identity, law, actions

Apr-June 2025 Perspective and Declaration

July-September 2024 Newsletter